Plantation

Life

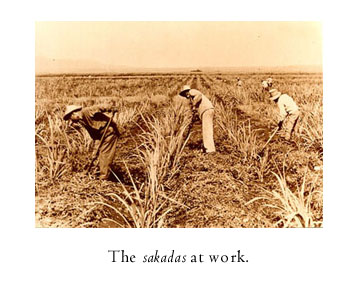

A

1919 report by a Philippine investigator, Prudencio

Remigio, tasked to investigate plantation conditions

stated that the Filipino sakadas complained of

inadequate wages, poor housing, abusive plantation foreman

or luna, strict plantation police, and general

isolation. Plantation work was extremely difficult since

it involved planting, hoeing, and carrying sugar cane.

The Ilocanos were not used to this rigid, punishing

working schedule. In Ilocos, they did not have to work

as many hours and were not subject to a strict system,

where the luna went around with a black whip

and forced them to work strenuously for so many hours.

The luna was backed by a police force capable

of breaking down workers' resistance. A

1919 report by a Philippine investigator, Prudencio

Remigio, tasked to investigate plantation conditions

stated that the Filipino sakadas complained of

inadequate wages, poor housing, abusive plantation foreman

or luna, strict plantation police, and general

isolation. Plantation work was extremely difficult since

it involved planting, hoeing, and carrying sugar cane.

The Ilocanos were not used to this rigid, punishing

working schedule. In Ilocos, they did not have to work

as many hours and were not subject to a strict system,

where the luna went around with a black whip

and forced them to work strenuously for so many hours.

The luna was backed by a police force capable

of breaking down workers' resistance.

The

HSPA adopted a "divide-and

-rule" policy whereby workers of different ethnicity

were pitted against each other for the purpose of keeping

wages down. In cases of strikes, one ethnic group would

be used as scab labor to break the strike of another

ethnic group. Living arrangements, job assignments,

and wages were also based on ethnicity. Caucasians were

higher paid, considered skilled workers, and assigned

supervisory positions. The lowest paid white worker

was the plantation police who earned $140 a month. In

contrast, the Japanese and the Filipinos were assigned

the backbreaking work in the fields. They worked at

least 10 hours a day, six days a week, 27 days a month

for 90 cents a day or $20/month.

Response

of Workers in Hawaii

In

his study of Hawaii plantations, Ronald Takaki states

that the workers’ response was resistance which

took several forms. Workers resorted to violence like

committing arson and assaulting the luna. A subtle

form of response was recalcitrance such as work slowdown,

intentional laziness, and inefficiency. Workers took

turns serving as lookouts for the luna while

the rest stopped working, smoked, and "talked story".

But Takaki notes that due to excessive fear among workers,

recalcitrance was not flaunted.

Strike

was another response of the workers. In 1909 Oahu witnessed

the Great Strike by Japanese laborers who demanded higher

wages and an end to the discriminatory wage differential

based on ethnicity. To counter the strike, Filipinos

were recruited to replace the vacated jobs. This marked

the first massive immigration of Filipinos to Hawaii.

In 1920 a larger, more organized strike occurred on

Oahu, this time by Japanese and Filipino laborers demanding

a wage hike and a change in the bonus system. The strike

ended after a six month standoff by which time the workers

received some concessions such as increased wages, abolishment

of wage differentials, and changes in the bonus system.

Takaki claims that the biggest gain in these strikes

was the realization that "blood unionism",

i.e., organizing workers into unions on the basis of

ethnicity, had to be replaced by a larger, class-based

solidarity as was displayed by the inter-ethnic alliance

of the Japanese and Filipino laborers.

The

Filipinos were organized as a result of the efforts

of two Filipino labor leaders: Pablo

Manlapit and Carl

Damaso. In her study of Manlapit, Melinda Tria Kerkvliet

claims that his leadership was displayed in the 1920

and 1924 strikes. In the 1920 strike, Manlapit believed

that the Japanese and the Filipinos should be united.

After the two month strike ended, Manlapit became the

subject of a smear campaign by the sugar planters and

he was accused of extorting money in exchange for calling

off the strike. But it was the 1924 strike which proved

fatal for Manlapit’s career. The strike had a tragic

ending when the police and strikers clashed in Hanapepe,

Kauai, resulting in the death of 20 people. Since Manlapit

was at the forefront of the strike, sugar planters hounded

him by filing various charges such as failure to provide

adequate water closets (toilets) for the evicted strikers

who were lodged temporarily in Kalihi. A conspiracy

charge was filed against him after he was said to have

coached a striker, Pantaleon Enayuda, to falsely claim

that his (Enayuda’s) sick baby died after the Oahu

Sugar Company, which managed the Waipahu hospital, ordered

the removal of the baby. Manlapit was found guilty of

libel and Enayuda turned witness against Manlapit for

the conspiracy case. Manlapit was imprisoned and later

deported from the islands.

Another

prominent Filipino labor leader was Carl Damaso who

came to Hawaii as a seventeen year old worker during

the height of the depression in the 1930s. In 1934,

he joined a strike of his fellow Filipino workers at

Ola’a Sugar Plantation - also known as Puna Sugar

Company - in the Big Island. The Filipinos, who made

up 70% of the plantation workforce, protested the lowering

of wages and the employment discrimination policy. The

strike was defeated and Damaso was branded a labor agitator

and placed on the list of "do not hire". He

moved to Maui and found work at the Wailuku Sugar Company

but was soon fired for attempting to start a union.

It was after World War II that he became a prominent

labor leader when he organized the International Longshoremen’s

and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU).

|