Labor

Migration in Hawaii

In

contrast to the pensionados, most of the Filipino

migrants to the United States during the colonial period

came as cheap labor. During the first half of the twentieth

century, Hawaii and California had agricultural economies

requiring a constant supply of inexpensive, immigrant

labor. Hawaii’s economy focused on sugar growing

supported by plantation labor.

To

sustain the constant demand for labor, the Hawaiian

Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) conducted a systematic,

organized recruitment of Filipino laborers. Labor recruiters

went to the Philippines and set up recruitment centers

in Vigan, Ilocos Sur,

and Cebu. In 1906 the first fifteen Filipino laborers,

all Tagalogs, came to Hawaii. Initially, the Filipinos

were averse to come to Hawaii because of the distance

and the wild rumors of alleged animals roaming the islands

and devouring the people. But recruitment campaigns

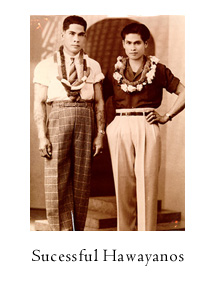

persisted and the "success" stories of the

first repatriated Filipino sugar workers or sakadas,

called "Hawayanos" in the Philippines,

eventually encouraged Filipino migration. To

sustain the constant demand for labor, the Hawaiian

Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) conducted a systematic,

organized recruitment of Filipino laborers. Labor recruiters

went to the Philippines and set up recruitment centers

in Vigan, Ilocos Sur,

and Cebu. In 1906 the first fifteen Filipino laborers,

all Tagalogs, came to Hawaii. Initially, the Filipinos

were averse to come to Hawaii because of the distance

and the wild rumors of alleged animals roaming the islands

and devouring the people. But recruitment campaigns

persisted and the "success" stories of the

first repatriated Filipino sugar workers or sakadas,

called "Hawayanos" in the Philippines,

eventually encouraged Filipino migration. The

exodus of Filipinos to Hawaii was reflected in the statistics.

In 1907, 150 Filipinos arrived in Hawaii. By 1909, 639

workers came and by 1910, there were 2,915. From 1911

to 1920, an estimated 3,000 workers arrived yearly.

In 1919, there were 24,791 Japanese workers and 10,354

Filipinos representing 54.7% and 22.9% respectively

of the total plantation labor force. The 1920s saw an

average of 7,630 Filipinos arriving in Hawaii annually.

In the 1930s, Filipinos had replaced the Japanese as

the largest ethnic group of workers in the plantations.

This was despite a temporary halt in the influx of Filipino

migrants in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression.

As a result of the Depression, a total of 7,300 sakadas

were repatriated to the Philippines.

In

1935, the Tydings-McDuffie

Law was passed. Aside from creating the Philippine

Commonwealth, a ten year transition government prior

to Philippine independence, the law also restricted

immigration to the U.S. to only fifty Filipinos each

year. The HSPA lobbied the U.S. Congress and was able

to gain exemption from the law which guaranteed a steady

Filipino labor supply until the onset of World War II.

Reasons

for Filipino Migration to Hawaii

After

the initial hesitation, Filipino migrant workers came

to Hawaii because they perceived the islands as glorya

(glory), a paradise of happiness and prosperity.

Many of them came to Hawaii for the purpose of saving

money to return home and live comfortably, i.e., to

be able to buy their own house and lot, till a small

farm, and get married. Until the 1940s most of the Filipino

sakadas believed that they were only temporary

residents of Hawaii.

Although

the initial migrants were Tagalogs, succeeding ones

were almost entirely Ilocanos. Due to the harsh living

conditions and the limited economic opportunities in

the Ilocos region, Ilocanos have been migrating to different

parts of the Philippines since the nineteenth century

to seek better fortunes. In the twentieth century, Hawaii

and California were the most appealing destinations

for adventurous Ilocanos.

Preference

for Filipino Workers in Hawaii

Hawaii

sugar planters preferred to import Filipino labor for

several reasons. First, since the HSPA paid the Filipinos

the lowest wage among the different ethnic groups in

the plantation, it was cheaper to import Filipino laborers

even if they were provided free passage to Hawaii. Second,

since the Philippines was a U.S. colony and the Filipinos

were technically U.S. nationals due to their colonial

status, from the legal standpoint it was practical to

hire Filipinos. As U.S. nationals, there were not covered

by the exclusion laws barring the importation of the

other so-called "Orientals," mainly Chinese

and Japanese. Third, Filipinos were viewed as a leverage,

an alternative labor to use against Japanese workers

who were staging strikes to improve their conditions

in the plantations. Fourth, because the Philippines

was an agrarian country exposed to sugar growing, the

HSPA felt that the Filipinos were suitable as sakadas.

But sugar was not grown in Ilocos, thus Ilocanos, who

comprised the bulk of the Filipino sakadas, were

not really exposed to the its harsh working conditions.

Fifth, the Filipinos were perceived to be docile, subservient,

and uneducated and, therefore, would not join labor

unions and be prone to strikes. Finally, the Filipinos

proved to be industrious and hardworking.

The

Filipinos who migrated to Hawaii were rural folks, many

of whom had few years of education. The HSPA preferred

to hire uneducated workers who knew nothing about their

legal rights. The migrant workers faced numerous problems

from the time they left the Philippines. While most

of them were Ilocanos, there were also a few Bisayans

or Tagalogs. Upon reaching Hawaii, they had to deal

with more ethnic diversity. Linguistic differences hampered

the workers’ ability to communicate with each other.

It was also difficult to deal with the loneliness since

they traveled without their women and family. But the

worst problem was the long hours of strenuous, back-breaking

hard work.

|