Proclamation

of Philippine Independence

and the Birth of the Philippine Republic

With

transportation provided by the Americans, Aguinaldo

and his leaders returned to Cavite. They resumed their

war offensive against Spain and reestablished the

revolutionary government. Because of the exigencies

of the time, Aguinaldo temporarily established a dictatorial

government, but plans were afoot to proclaim the independence

of the country especially since the Spaniards were

reeling from defeat one battle after another.

From

the balcony of his house in Kawit, Cavite, Aguinaldo

declared on June 12, 1898 the independence of the

Filipinos and the birth of the Philippine Republic.

For the first time, the Philippine flag, sewn in Hongkong

by the womenfolk of the revolutionaries, was unfurled.

Two bands played Julian Felipe’s Marcha Nacional

Filipina which became the Philippines’ national

anthem. The declaration further emboldened the fighting

Filipinos.

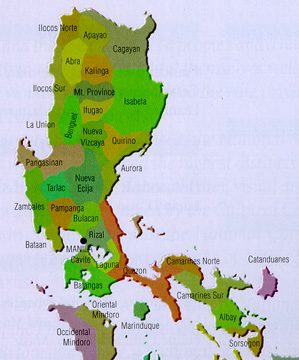

On

June 18, 1898, Aguinaldo passed a decree calling for

the reorganization of the provincial and municipal

governments. In her article, Guerrero claims that

following the liberation of Luzon from the hands of

the Spaniards, elections were held in Cavite, Bataan,

Batangas, and Pampanga in June and July; in Manila,

Tayabas (now Quezon), Pangasinan, Ilocos Norte, and

Ilocos Sur in August; in Abra, Camarines Norte, Camarines

Sur, and Nueva Ecija in September; in Nueva Vizcaya

and La Union in October; and in Isabela, Catanduanes,

Albay, and Sorsogon in December. The elected provincial

and town officials were mostly the same local officials

during the Spanish period. This was because the requirements

for voting and nomination to public office were restricted

to those who were "citizens of 20 years of age

or above who were ‘friendly’ to Philippine

independence and were distinguished for their ‘high

character, social position and honorable conduct,

both in the center of the community and the suburb’."

On

June 18, 1898, Aguinaldo passed a decree calling for

the reorganization of the provincial and municipal

governments. In her article, Guerrero claims that

following the liberation of Luzon from the hands of

the Spaniards, elections were held in Cavite, Bataan,

Batangas, and Pampanga in June and July; in Manila,

Tayabas (now Quezon), Pangasinan, Ilocos Norte, and

Ilocos Sur in August; in Abra, Camarines Norte, Camarines

Sur, and Nueva Ecija in September; in Nueva Vizcaya

and La Union in October; and in Isabela, Catanduanes,

Albay, and Sorsogon in December. The elected provincial

and town officials were mostly the same local officials

during the Spanish period. This was because the requirements

for voting and nomination to public office were restricted

to those who were "citizens of 20 years of age

or above who were ‘friendly’ to Philippine

independence and were distinguished for their ‘high

character, social position and honorable conduct,

both in the center of the community and the suburb’."

These

provisions automatically excluded the masses in the

electoral process, and insured continued elite supremacy

of local politics, even by those who were Spanish

supporters and sympathizers during the early phase

of the Revolution. Since the ilustrados had

exclusive control of the electoral process, the provincial

and municipal reorganization merely resulted in perpetuating

elite dominance of society and government. Guerrero

claims that records of the period reveal the composition

of the municipal elite was unaltered and local offices

simply rotated within their ranks.

But

not all areas of Luzon came under the control of the

ilustrados during the Revolution. In some towns,

"uneducated" and "poor" masses

were elected by an electorate who most probably did

not meet the qualifications stipulated in Aguinaldo’s

decree. Guerrero claims that the principalia

or ilustrado local officials of Solano in Nueva

Ecija and Urdaneta in Pangasinan complained over the

election of the "uneducated and ignorant"

who they argued were "totally incapable"

of governing. But this was more of an aberration since

the general picture was one of elite dominance and

the alienation of the masses. Despite Aguinaldo’s

order abolishing three hundred years of Spanish polo

or forced labor, the local elite persisted in demanding

personal services from the people, on top of the taxes

levied against them. In some towns and provinces conditions

were even worse as the elite wrangled among themselves,

especially since Aguinaldo did not clearly delineate

the responsibilities of the elected civilian and appointed

military officials. This leads some historians to

conclude that the masses in towns and countryside

were the eventual victims of what transpired during

the Revolution.

The

American entry into the picture convinced the remaining

fence-sitting ilustrados to support the Revolution.

When rumors of an impending Spanish-American War were

circulating in April 1898, several noted ilustrados

led by Pedro Paterno offered their services to the

Spanish governor-general. Yet when Aguinaldo returned

from exile, several ilustrados serving in the

Spanish militia, like Felipe Buencamino, abandoned

the Spaniards and announced their "conversion"

to the revolutionary cause. Indeed, the resumption

of the revolution brought an electrifying response

throughout the country. From Ilocos in the north down

to Mindanao in the south, there was a simultaneous

and collective struggle to oust the Spaniards.

Months

later, when the Filipino-American War commenced, many

ilustrados played the middle ground, i.e.,

on one hand, they sent words of support to Aguinaldo

and, on the other, started contemplating on an autonomous

status for the Philippines under the United States.

An example was the Iloilo ilustrados who eventually

sided with the Americans since their economic interests

- sugar production and importation - dictated collaboration

with the new colonizers. Indeed, in the parlance of

contemporary Filipino political culture, the ilustrados

were the classic "balimbing" or two-faced.

Despite

the constant vacillation of the elite, Aguinaldo and

his advisers tapped on their services in organizing

the Philippine Republic. Aguinaldo was eager to prove

that the Filipinos could govern themselves, and in

the process it would legitimize the Philippine Republic.

Moreover, since he and his advisers were ilustrados,

Aguinaldo only trusted his own kind - the wealthy,

educated, and politically experienced - in the matter

of governance. Thus, he called on them to convene

and create a Congress which would draft a constitution.

He wanted a Philippine constitution to complete the

required trimmings of a sovereign, nation-state -

flag, army, government, and constitution. In his actions,

Aguinaldo was advised by Apolinario

Mabini who became known as the "Sublime Paralytic"

because his spirit was not deterred by his physical

handicap, and the "Brains of the Revolution"

due to his intellectual acumen. On January 21, 1899,

Aguinaldo proclaimed the Malolos Constitution which was drafted by the

ilustrados of the Malolos Congress. Two days

later, the Philippine Republic was inaugurated in

Malolos, Bulacan, the new capital of the fledging

government.

The

Philippine Republic was, however, short-lived. From

the start, Aguinaldo’s forces were fighting the

Spaniards without military assistance from the Americans.

Except for the Battle of Manila Bay, the United States

was not a major force in the fighting. The American

troops did not arrive in the country until late June,

and they saw no military action until August. But

events starting with the Spanish surrender of Manila

on August 13, 1898, doomed the end of Philippine independence.

Although

the Spanish troops had been routed in all fronts by

the Filipinos, the continuing presence of the Americans

was unsettling. Questions on actual American motives

surfaced with the continuous arrival of American reinforcements.

It did not take long for the Filipinos to realize

the genuine intentions of the United States. The precarious

and uneasy Philippine-American alliance collapsed

on February 4, 1899, when the Philippine-American

War broke out and threatened to annihilate the new

found freedom of the Filipinos.