Ethnicity

and the Creation of National Identity

Initially,

the Revolution appeared to be an entirely Tagalog affair.

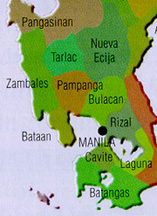

The first eight provinces to rise in arms were all in the

Tagalog region and its adjacent areas: Bulacan, Nueva Ecija,

Tarlac, Pampanga, Manila, Laguna, Cavite, and Batangas. Even

among these provinces, fighting was minimal except for Cavite,

Bulacan, and, of course, Manila. Most of the principal revolutionary

leaders were Tagalogs, and their initial appeal of support

was directed towards the Katagalugan or the Tagalog

people. This was not surprising since prior to the Revolution,

Filipinos did not think of themselves as one homogenous race.

Identity was instead linked with regional ethnicity. The Spanish

policy of divisiveness aimed at effecting colonial rule promoted

and encouraged regional isolation and ethnic distinctions.

By the nineteenth century the term "Filipino" referred

to the Spanish insulares or those born in the Philippines.

The Filipinos in general were loathingly called indios

and their identity was rooted on their regional origin or

ethnic affiliation: Tagalog, Kapampangan, Cebuano, Ilocano,

Ilonggo, etc.

In the

first two years of the Revolution, battles raged mainly in

the Tagalog provinces. Outside the Katagalugan, responses

were varied. Pampanga, which was close to Manila, was uninvolved

in the Revolution from September 1896 to the end of 1897,

perhaps because the conditions which drove the Tagalogs to

rise in arms were not totally similar in Pampanga. For instance,

friar estates or church monopoly of landholdings which triggered

agrarian unrest in Tagalog areas was not pervasive in Pampanga.

Besides apathy, there were those, such as some Albayanos of

Bicol, who were even apprehensive of rumors of a "Tagalog

rebellion" aimed at ousting the Spaniards and exercising

Tagalog hegemony over the non-Tagalog ethnic groups. Historian

Leonard Andaya claims that what brought the Revolution to

the non-Tagalog areas was Aguinaldo’s policy of encouraging

his military officials to return to their home province and

mobilize local support. For instance, the Revolution came

late in Antique, and it was due to General

Leandro Fullon, an Antiqueno principalia general

of Aguinaldo, who went to his home province to spread the

Revolution. Even after the Revolution spread to the rest of

Luzon and the Visayas, there were still suspicions as to the

real motives of the Tagalogs. For example, the Iloilo elite

changed the name of their provisional revolutionary government

and called it the Federal State of the Visayas since they

did not want to recognize the supremacy of Aguinaldo and the

Tagalogs. They preferred instead a federal arrangement composed

of the three main island groups - Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

These

reservations and suspicions by non-Tagalogs were somehow reinforced

by the initial writings and proclamations of key Tagalog personalities

of the Revolution. Bonifacio wrote a revolutionary piece which

he entitled "Ang Dapat

Mabatid ng mga Tagalog" or "What the Tagalogs

Should Know." Aguinaldo, in his memoirs, wrote chapters

entitled "The Tagalog Government Begins" and "Long

Live the Tagalogs." But in the absence of a general,

generic term to collectively refer to the inhabitants of the

archipelago, Filipino being a term originally reserved for

the Spanish insulares, Tagalog may have appeared to

the leaders of the Revolution as a logical substitute because

of its indigenous element.

In

due time, however, Aguinaldo’s proclamations gradually

introduced the idea that all the inhabitants of the Philippines

are Filipinos. Tagalog became less used and in its place

Filipino was increasingly mentioned. The Revolution likewise

assumed a national character. The declaration of Philippine

independence was both significant and symbolic in the imagining

and forging of a Filipino nation-state. Although there was

a gradual acceptance of the term Filipino, nonetheless up

until the early American period, Tagalog was still occasionally

used. General Macario Sakay,

a Tagalog general who continued the war against the Americans

even after Emilio Aguinaldo was captured, called his government

in 1902 the Tagalog Republic, although its charter noted

that Visayas and Mindanao were included in his Republic. In

due time, however, Aguinaldo’s proclamations gradually

introduced the idea that all the inhabitants of the Philippines

are Filipinos. Tagalog became less used and in its place

Filipino was increasingly mentioned. The Revolution likewise

assumed a national character. The declaration of Philippine

independence was both significant and symbolic in the imagining

and forging of a Filipino nation-state. Although there was

a gradual acceptance of the term Filipino, nonetheless up

until the early American period, Tagalog was still occasionally

used. General Macario Sakay,

a Tagalog general who continued the war against the Americans

even after Emilio Aguinaldo was captured, called his government

in 1902 the Tagalog Republic, although its charter noted

that Visayas and Mindanao were included in his Republic.

|