LOYALTY AND VALOR: HAWAI'I'S FILIPINO AND

FILIPINO AMERICAN SOLDIERS

The Philippine Scouts and

the 1st & 2nd Filipino Regiments

In 1898, after Emilio Aguinaldo’s Cavite revolutionary forces burned down San Nicolas de Tolentino Church with 300 worshipers still inside, the townspeople of Macabebe, Pampanga asked the Americans—their new colonizer—to liberate their town. On May 1, 1899, the Americans liberated Macabebe, after which the Macabebes pledged to guide the Americans to chase Aguinaldo. Thus was born the Macabebe Scouts, the first contingent of America's elite Philippine Scouts. Other units would soon follow from Negros, Samar, Ilocos, Cagayan and even from Tagalog regions.

Forming a colonial army made up of native troops supplementing the colonizing army was a practice previously utilized with Native American tribes. These native soldiers not only knew the local languages and terrain, they were fierce fighters and proved to be loyal to the American regime. Major Matthew Batson, commander of the Macabebe Scouts said of his unit: They are fearless in battle, and it is almost impossible to ambush them. They are expert swimmers, always cheerful, always obedient to orders.

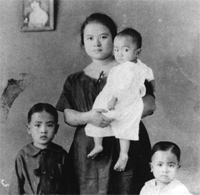

Scout uniforms, rations, and equipment were similar to those of Regular Army troops, but they were initially equipped with outdated weapons and received about one-third the pay of U.S. regulars. By 1914, however, a few Filipinos were admitted to West Point to train as officers for Scout units. In the 1920’s fifty Philippine Scouts, twenty-three wives and their seventeen children transferred to Hawai'i to join the U.S. Army Hawaiian Division. Although they had combat training, these former Scouts were selected because of their additional skills as cooks and musicians. Married soldiers were assigned homes in a barrio-like community—a cluster of houses located over a mile from other families in Wheeler Air Field, named Castner Village. This "segregation" forced families to develop their own Filipino identity in Hawai'i, distinct from other military families and, significantly, from other Filipinos living in nearby plantation camps.

Soldiers were assigned to one of eight regimental bands to perform at military ceremonies and athletic events. Many musicians also worked in the base’s kitchen. Over time, family members would develop and apply their musical talents while others continued their family tradition in distinguished careers with the military. Following the Pearl Harbor attack the Hawaiian Division would be reorganized into the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions. Both units would eventually participate in the Philippines Campaign..

At the time Japan attacked the Philippines, the Scouts numbered approximately 8,000 men in the Philippine Division and separate units. Following the surrender of all American forces, thousands of Scouts escaped capture and continued to fight their newest invaders in guerrilla warfare. Their example of loyalty to the U.S. and perservance amid overwhelming odds and conditions was a reassuring symbol for Filpinos and Americans waiting for liberation. They would eventually heed the call by General MacArthur to regroup and continue their service to the United State as the "New Philippine Scouts." For their service, the organized guerrilas were promised the same health and pension benefits as their American brothers and were to be treated like any other American veterans.

Clandestine operations were conducted to support the guerrillas by smuggling guns, radios and supplies to them by submarine. These guerrilla units, led by Filipinos and Americans, organized and transmitted detailed reconnaissance information to MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia, sabotaged Japanese installations and communications, and laid the groundwork for the eventual liberation of the Philippines. After the American landings, their participation in rescue missions of prisoners held in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija and Los Baños, Laguna was indispensible to the raids' success.

Following the invasion of the Philippines by Japan, thousands of Filipinos petitioned for the right to serve in the U.S. military. On January 2, 1942, President Roosevelt signed a law revising the Selective Service Act allowing Filipinos in the U.S. to enlist in the U.S. Armed Forces. President Roosevelt quickly authorized the founding of a Filipino battalion and, on March 4, 1942, the 1st Filipino Battalion was formed. The War Department also directed Philippine army officers and soldiers who were stranded in the United States at the start of the war to report to the unit.

The response of Filipinos on the U.S. continent to enlist was so overwhelming that in three months the 1st Filipino Battalion became the 1st Filipino Regiment, activated in Salinas on July 13, 1942. On October 14th of the same year the 2nd Regiment was activated at Ft. Ord, bringing together a fighting force of more than 7,000 men. Many of the recruits were sturdy migrant farm laborers or educated pensionados and, with an average age of over 30 years, were highly motivated and well disciplined. Furthermore, with changes in the U.S. Naturalization Law, many Filipinos managed to become citizens in mass oath taking ceremonies.

Flipinos in Hawai'i faced a familiar barrier to enlist: the Hawaiian Sugar Plantation Association. HSPA argued successfully that Filipino laborers were necessary on the plantations to support the war effort and, additionally, Filipinos in Hawai'i were forbidden by the Tydings-McDuffie Act from going to the continental U.S. Eventually, in 1943, Filipinos deemed non-essential workers enlisted or were drafted as replacements in the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments. Identified as and referred to as Pineapples, Hawai'i's Filipinos were younger than the original recruits, who were called Pops, Grandpa, or Tata. The younger Hawaii recruits respected the experience and wisdom of their elders as much as the older ones enjoyed the Pineapples' easy-going friendliness, generosity and cockiness—especially regarding unreasonable orders. Nonetheless, what all 1st and 2nd Fil soldiers had in common was their rigorous training and facing prejudice.

Members of the Regiment often encountered prejudice, and California's anti-miscegenation laws prevented Filipino men from marrying non-Filipino women. Soldiers wishing to marry non-Filipino women were transported to New Mexico which had repealed its anti-miscegenation law after the Civil War. Local businesses in Marysville (near Camp Beale) refused to serve Filipinos until the Regiment’s commander reminded the Chamber of Commerce of Marysville's failure to cooperate with the Army was unacceptable, at which point they changed their business practices. More acts of discrimination against Filipinos were also reported in Sacramento and San Francisco.

HOME |

Filipino-American

Historical Society of Hawaii

|

Help

Exhibits

| Publications

|

Collections

| Student/Teachers

Photographs

& Maps | Biographies & Oral Histories

| Community Organizations

WWI

Veterans | Centennial

Commission (2006)

Copyright © 2006 by the Filipino-American Historical Society of Hawaii. Updated 2020.